About This Project

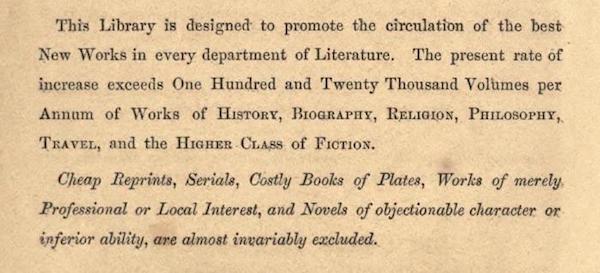

Since the closure of Mudie’s in 1937, a substantial body of scholarship has examined the library’s influence on the British publishing industry. The library’s own claim – that it only held works which conformed to the highest prevailing standards of moral rectitude – was a source of great concern for contemporary novelists and critics, many of whom felt that it represented a form of censorship. Recent studies (see Bibliography) have examined financial records and marketing materials alongside accounts of the library by contemporaries, and have expanded and provided nuance to our understanding of Mudie’s gatekeeping role. However, some key contemporary sources of information on the library – its own printed catalogues – have until now been comparatively neglected.

Although a number of the library’s catalogues and other marketing materials survive, and are available either in library archives or in some cases as scanned PDFs, the enormous extent of the library’s collection has made it difficult to provide a comprehensive, user-friendly database of the library’s holdings. We have created this resource in order to provide readers with an understanding of what was available to the average subscriber of a circulating library in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Mudie's Library Online was developed as part of the European Research Council (ERC) funded project VICTEUR - European Migrants in the British Imagination: Victorian and Neo-Victorian Culture, a collaboration between the UCD School of English and the SFI-funded Insight Centre for Data Analytics.

Catalogues

This database incorporates the complete fiction listings from a number of Mudie’s catalogues, selected to try and represent as complete a picture of the library’s nineteenth-century history as possible. More catalogues are in the process of being added. The collection currently consists of:

- 1848/1849: adapted from a copy held by the Guildhall Library, London

- 1857: adapted from a copy provided by Google Books

- 1860: adapted from a copy provided by HathiTrust

- 1865: adapted from a copy provided by HathiTrust

- 1876: adapted from a copy provided by The Internet Archive

- 1885: adapted from a copy acquired and scanned by the VICTEUR project team here

- 1895: adapted from a copy acquired and scanned by the VICTEUR project team here

- 1907: adapted from a copy provided by The Internet Archive

Frequently Asked Questions

Q. Which catalogues are represented in the database?

Currently, the database is comprised of the fiction listings from the following 8 catalogues:

| Year | Number of unique titles |

| 1848-9 | 797 |

| 1857 | 1,257 |

| 1860 | 1,428 |

| 1865 | 2,198 |

| 1876 | 3,526 |

| 1885 | 4,858 |

| 1895 | 8,393 |

| 1907 | 15,418 |

Mudie's did not print a new catalogue every year, and (to the best of our knowledge) some catalogues are no longer extant. We are hoping to add additional catalogues to the database during the lifespan of the project. A total of 22,040 unique works are currently indexed by this database, where around half of these appear in more than one catalogue.

Q. What information do the catalogues provide?

Catalogues typically include introductory material (including regulations and subscription rates) and book listings, which are usually split into non-fiction and fiction.

Within the listings for each book, the catalogues list the title, and generally (although not always) the name of its author. Some catalogues also provide a basic description of each novel (see the explanation of book descriptions, below).

The 1907 catalogue contains a number of additional sections, including juvenile fiction and a section in which books are listed by genre. We are hoping to include some of this information in later editions of the dataset.

Q. Do you include non-fiction in this database?

Unfortunately, the scope of the project does not currently extend to non-fiction.

Q. Is this an exact replica of the original listings from the catalogues?

We have tried to reproduce the catalogue listings as accurately as possible, but in some cases, for clarity, we have provided additional information. For example, we now know the identity of the authors of many works which were first published anonymously, and we have provided this information where possible. Every effort has been made to ensure that the database is accurate, but a small number of errors may still remain. We would greatly appreciate being appraised of any mistakes or duplicate entries, at mudieslibraryonline@gmail.com.

Q. Where can I find original copies of these catalogues?

PDF versions are available for 1857, 1860, 1865, 1876, 1885 (fiction only), 1895 (fiction only), and 1907.

Other catalogues in PDF format which have not been included in this project can be found here 1859, 1873, 1911. Two catalogues of works in European languages other than English are also available: 1868, 1907.

Archives which are known to hold original physical copies of Mudie’s catalogues include the Guildhall Library (which contains the original of our 1848/9 catalogue) and the Bodleian Library.

Q. Do the catalogues include everything Mudie’s ever stocked?

Anecdotal evidence suggests that Mudie’s stocked some works that were not listed in the catalogue, either accidentally or deliberately. The library seems to have kept copies of certain controversial works which it did not choose to advertise, but could still be requested specially by customers. (See Griest, pages 214-15, for a discussion of this practice.) Additionally, certain gaps in our data suggest that some older works may have languished in a back room without being catalogued in some years, only to reappear later.

Q. How have you assigned authorial gender?

Part of this project’s goal is to better understand gender representation within the library – in particular, the representation of female novelists. In order to accomplish this, we have applied a basic scheme of gender to the authors whose works appear in the catalogues. We have described authors as "male" and "female" where known. "Unknown" is applied in cases where no indication of authorial gender was available to the project team, including works published anonymously. Where the author is only known by a pseudonym, we have used "Pseudonym". "Pseudonym?" indicates a suspected but unconfirmed nom de plume. In some cases we have used the term "Multiple", indicating that a group of otherwise unidentified writers worked on a title: examples include "Two Authors", "Society of Novelists", and "Puck’s Authors".

| Author assignment | Number of authors |

| Male | 3,146 |

| Female | 2,233 |

| Unknown | 534 |

| Pseudonym | 53 |

| Pseudonym? | 31 |

| Multiple | 9 |

| Total | 6,006 |

We have used a mix of biographical information and bibliographical sources in making these gender designations. However, we are conscious that this scheme lacks nuance, both in terms of historical understandings of gender and in accounting for the complexities of authorial identification. We may also have incorrectly categorised specific authors. We would be grateful for any corrections or additional information you may have to offer on the novelists featured here; you can contact us at mudieslibraryonline@gmail.com.

Q. What do the book descriptions refer to?

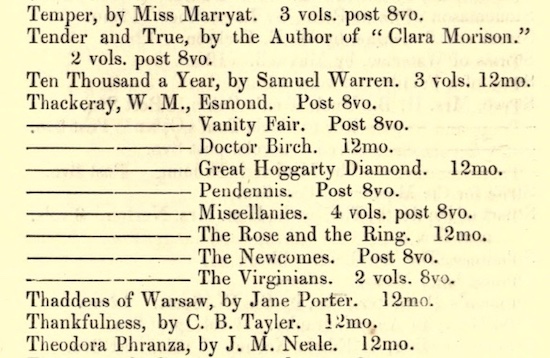

Some of the catalogues provide information on each book’s size and the number of volumes it comes in. These descriptions are available for the years 1857, 1860, 1865, 1876, 1885, and 1895, but they do not appear in our earliest and latest catalogues (1848-9 and 1907).

Book size is usually indicated with one of the terms "octavo/8vo", "post octavo", "duodecimo/12mo", or "small octavo", with a few less common terms making an occasional appearance ("foolscap octavo", "royal octavo", "octodecimo/18mo"). These terms refer to the size and paper fold styles used in the construction of the book. It appears that Mudie’s did not use these terms consistently, as they frequently change for the same listing between different catalogues, and almost every book labelled "duodecimo" in 1860 appears as "small octavo" in 1876. However, at times they may be helpful for identifying the specific edition of a work which is held in the library.

Volumes indicates whether a book was published in one, two or three (or sometimes more) individual volumes. Mudie’s was widely believed to prefer three-volume novels, as these were the most prestigious (and expensive) publication format, and were also the most cost-effective for the library, in that they encouraged subscribers to upgrade from the basic subscription (one guinea a year for one volume at a time) to a more expensive subscription that would allow four or eight volumes at a time (Nesta 2007). Contrary to accepted tradition, however, "triple-deckers" were relatively unusual, comprising no more than 40% of novels stocked in any of the catalogues.

Typically, somewhat under 20% of the novels in our catalogues were originally published in two volumes. If we assume that all listings not otherwise designated were for single volume novels, these comprised the bulk of the collection, accounting for as much as 59% of all listings in 1860. Occasionally, Mudie’s may have rebound triple-decker editions of older novels into a single volume in order to save space. At times, though, they appear to have declined an expensive three-volume novel on its first publication, waiting until its success was proven by the appearance of a second edition (usually in a single volume) in order to buy it in for the library.

Q. Where can I access full versions of the novels which are listed here?

We don’t yet have direct links to the original texts, but hope to add this feature in future versions of the project. The vast majority of these novels have been digitized, and can be located via either the Internet Archive, HathiTrust, or Google Books collections. Some may also have been proofread and adapted for e-readers by Project Gutenberg. If a novel has not yet been digitized, the best resource to check is WorldCat, which will direct you to the nearest library that holds a physical copy of the text.

Q. What are the fiction classifications, and why do some Author pages contain "Subject area(s)"?

The Mudie’s 1907 catalogue contains a section (found on pages 676-724) titled "Fiction Classifications", which lists 4890 titles, or around a third of all the novels in the catalogue, under various thematic headings. The system of categories and sub-categories appears to be specific to Mudie’s. You can browse the fiction classification index here (PDF).

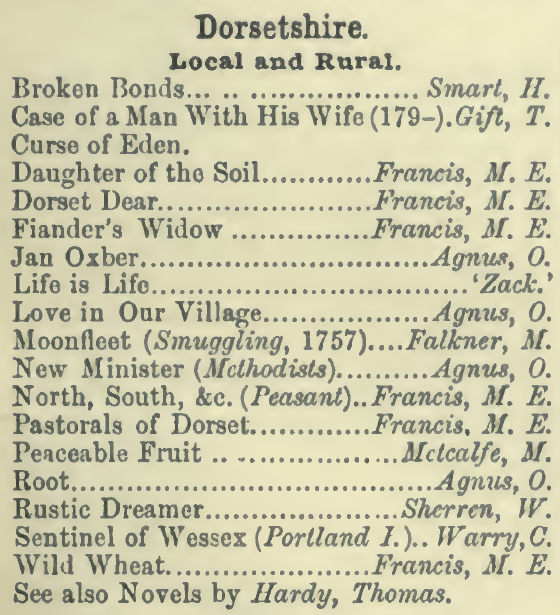

This index primarily lists the titles of individual novels, but certain authors are also named, indicating that some or all of their novels also deal with the specified topic. For example, below you can see the titles which Mudie’s suggests are related to "Counties and Towns/Historical and Topographical/Dorsetshire/Local and Rural" (found on page 695). At the end of this list, Thomas Hardy is indicated as an author whose works are also concerned with local and rural life in Dorsetshire.

We have integrated all of the fiction classification data into the author listings, and intend to update the site with the listings for titles.

Q. What are the fiction classifications, and why do some Author pages contain "Subject area(s)"?

The classifications are extensive, but not exhaustive – as mentioned above, they cover only about a third of the fiction from the Mudie’s 1907 catalogue. The index is skewed toward the end of the century: the majority of the listed titles date to the 1890s or early 1900s, which suggests that they are likely to have been recently acquired by the library. (When older novels appear in the index, they tend to be ones which were very well-known by 1907.) Since the index does not represent the collection in its entirety, it may be most useful as a demonstration of the categories and hierarchies which were considered relevant to librarians and the patrons they served. It is also worth noting that the classifications listed in the index are representative of modes of thought which were current when the catalogue was compiled, and consequently, they contain some outdated (and in some cases offensive) language.

Despite some drawbacks, the index provides a substantial amount of interesting and potentially very useful information on the works in the collection. The hierarchical structure of the classifications provides insight into the ways in which the librarians understood the contents of their collection, and indeed, how contemporary readers may have viewed genres. For example, a number of books that we might nowadays consider "science fiction" have been split across several different lists, including "Aerial and Stellar adventures" (which lists H. G. Wells's The First Men in the Moon), "Mysterious and Marvellous" (which lists Shelley's Frankenstein), and "Forecasts" (which lists Samuel Butler's Erewhon).

Additionally, many novels have been annotated with brief notes which provide more specific information about their contents. A large number specify the exact date in which they are set, ranging from Arthur S. Way's David the Captain, set in 1040 B.C., to The Sack of London by "Jingo Jones", set in 1901 (and published in 1900). Other types of information on the novels are provided, including specific locations (Sark, Warsaw, Barbados, Tonkin, West Australia, Kashmir); historical events (Persian conquest, Rebecca Riots, South Sea Bubble); historical personages (Salvatore Rosa, Dreyfus, Hadrian, de Pompadour); scientific developments (railways, vaccination, Rontgen); social developments and movements (Factory Life, Anti-Vivisection, Land League, Slavery Abolition); and cultural phenomena (violin, sculpture, mesmerism, touring, and legends from Sanskrit or from the Norse Saga Library).

Further Readings and Resources

At The Circulating Library: A Database of Victorian Fiction, 1837-1901 (Bassett) [Link]

British Fiction 1800-1829: A Database of Production, Circulation and Reception (Garside, Belanger, Ragaz, Mandal) [Link]

Bassett, Troy J. 'The Rise and Fall of the Victorian Three-Volume Novel'. Springer International Publishing AG, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central [Link]

Colclough, Stephen. 'New Innovations in Audience Control: The Select Library and Sensation’. Reading and the Victorians, edited by Judith John, Routledge, 2016

Finkelstein, David. '"The Secret": British Publishers and Mudie’s Struggle for Economic Survival 1861-64’. Publishing History, vol. 34, 1993

Griest, Guinevere L. Mudie’s Circulating Library and the Victorian Novel. David & Charles, 1970 [Link]

Keith, Sara. 'Literary Censorship and Mudie’s Library’. Colorado Quarterly, vol. XXI, no. 3, Winter 1973, pp. 359–72.

Nesta, Frederick. 'The Myth of the "Triple-Headed Monster": The Economics of the Three-Volume Novel’. Publishing History, vol. 61, 2007.

Roberts, Lewis. 'Trafficking in Literary Authority: Mudie’s Select Library and the Commodification of the Victorian Novel’. Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 34, no. 01, 2006, pp. 1–25. Cambridge Journals Online [Link]